Culinary Artist-in-Residence Sara Clugage shares the inspiration behind her 2024 Taste of Ox-Bow Dinner

by Sara Clugage

In August 2024, I created a Taste of Ox-Bow dinner featuring jelly. Evincing strong reactions from would-be eaters, jelly mixes delight and disgust, mirroring our confusion over what jelly is. Jellies cohere into masses that hold their boundaries—in the loosest sense of the term, they are bodies. They wobble and wiggle like bodies do, and this can give us the charming (or horrifying) idea that they might be just a little bit alive.

Working with these rendered bodies has opened up new conceptual territories for me around blobs and slumping, transparency and rigidity, fragility and permanence. I wanted to extend that research with two similar materials that often appear on dinner tables: glass and crystal.

Our cocktail hour started with blobs. Like jelly, glass starts out as liquid blobs that then solidify in place. We used pooling glass to heat small packets of shrimp; the blobby shrimp solidified as well, turning pink as the red-hot glass seeped into gray tones. A pineapple lime smash sloshed its liquid inside a glass garnished with a solidified cocktail “lime” hung on its rim—a jello shot set into a citrus rind.

A hand places sprouts along a crystalized jelly river. Photo by Dominique Muñoz (Summer Fellow 2024).

Like jelly and glass, crystal is transparent but its organizing structures are invisible. These are the material experiences we use to approach concepts that are hard to think about: things too abstract to mentally grasp and things that ooze between the categories of animate and inanimate. Jelly shows up as a metaphor for things that are real-but-unreal, alive-but-not, in an astounding variety of fields: chemistry, evolutionary biology, anthropology, educational reform, and political economy. This array of disciplines has picked up on ideas already theorized and served up by cooks.

In designing a dinner at Ox-Bow, I thought about late 18th century tablescapes that incorporated jelly, along with sugar and salt crystals, into garden designs. These tablescapes were built from an imperial point of view, featuring focal elements that were, to the European mind, alluring fantasy structures: pagodas and temples and obelisks made out of crystals and jelly. Tablescapes and gardens are worldbuilding exercises; they sort the elements of our world into the places we want them to occupy and make them available for our consumption.

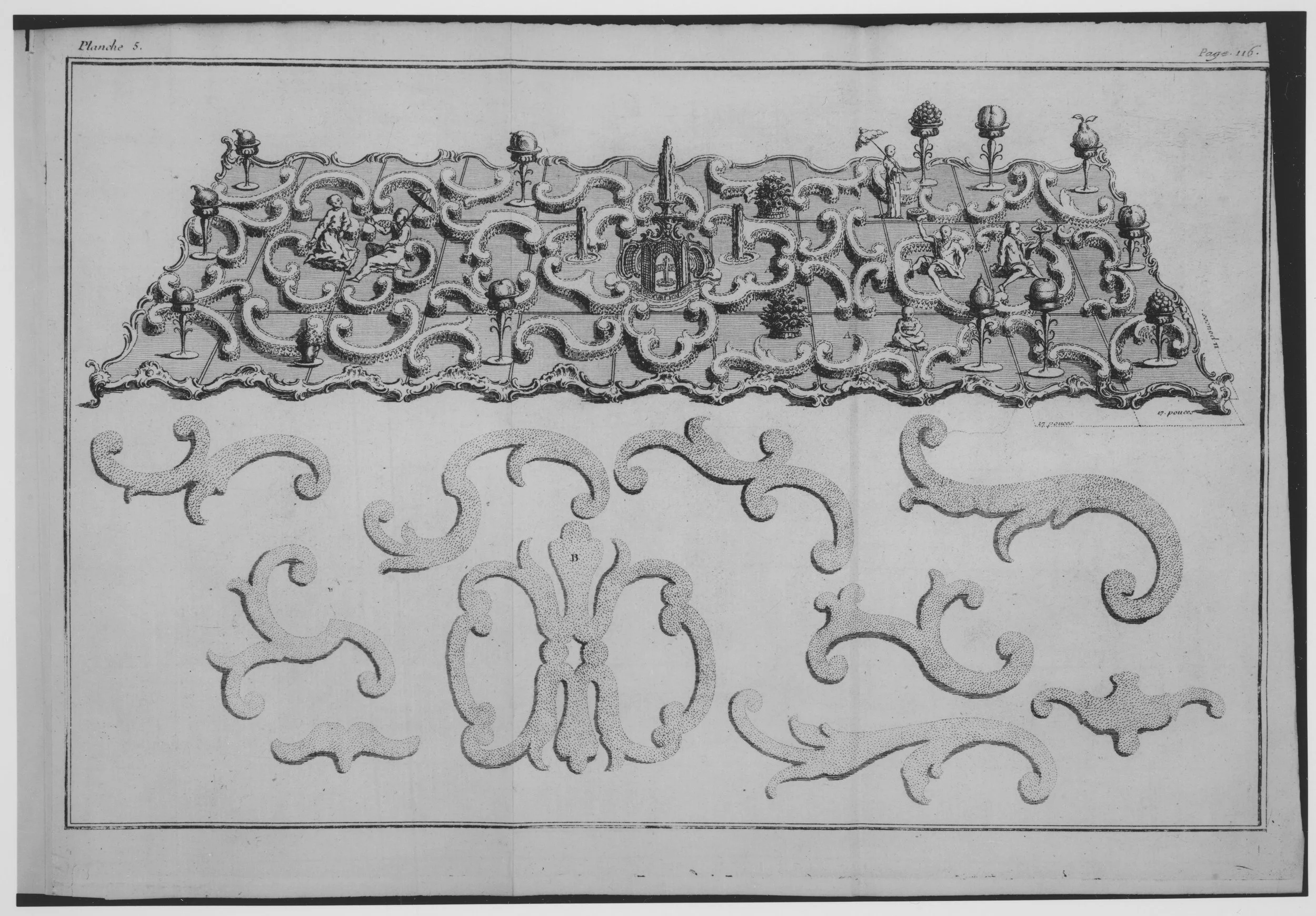

Joseph Gilliers, Le Cannameliste Français, Ou Nouvelle Instruction Pour Ceux Qui Desirent D'Apprendre L'Office, Rédigé en Forme de Dictionnaire. Image courtesy of Public Domain.

Consider this design by the confectioner Joseph Gilliers, published in 1751, that creates a whole garden world on a mirrored parterre. In the middle there’s an obelisk-like spun sugar fountain (perhaps calling up the Obelisk Fountain at Versailles), and Chinese-style figures are strolling or lounging among sweetmeats and fruit. The garden is defined by giltwood scrolls that resemble French hedges. The range of references reflects European state and market interests of the time: closer trade ties with Egypt, as Egypt moved toward independence from the Ottoman Empire, and Europe’s increasingly predatory trade with China.

Roughly contemporary with Gilliers’s design, Wedgwood first made this obelisk-style “pyramid mold” in 1780. Like the other elements in Gillers’s tablescape design, these pyramid jellies solidified the reach of the empire into new territories in Africa and Asia by making them present in the dining room. I find the use of jelly here particularly evocative because its movement brings the shape to life.

Sara Clugage, Yellow Jell-O, Pearlware enameled ceramic core from a "pyramid" or "core" mold (Wedgwood, c. 1780), painted in Japan Pattern 8, covered in lemon Jell-O. Photo by the author.

For Ox-Bow, I built a tablescape that was informed by Gilliers and Wedgwood but slanted sharply away from their worldviews. A mushroom dashi jelly river rushes down the table, held in bounds by frilly green banks of radishes and carrots. The outer border is a formal French parterre garden made with strips of parchment spread with butter and stenciled in black salt. The stencil design is inspired by the geometric beds in Versailles’ Orangerie, which themselves call back to earlier French garden style beds that were not planted with greenery but raked with sand.

A fully dressed table designed by Sara Clugage. Photo by Dominique Muñoz (Summer Fellow 2024).

This landscape could have remained perfectly still and uneaten in the middle of the table, as 18th tablescapes often did, but instead Ox-Bow diners altered and tended it as the meal progressed. For the first course, they swiped carrots and radishes through the butter and salt. Once the riverbeds had been admirably pruned, an algae bloom threatened: we spilled charred peas mixed with coffee oil and chili oil over the mushroom jelly river, then asked diners to clean up the “algae” by removing it to their pasta bowls (now filled with a butter shoyu pasta and the reserved dashi-soaked mushrooms). When the murk had been cleared, we ended the meal with a halo-halo style dessert: peaches and candied peanuts over peach ice cream, topped with carved lapsang-souchong jelly crystals in the Japanese kohakutou style. Finally cooled, a strict lattice had snapped into place in every jelly, aligning its protein molecules forever.

The tablescape now uprooted, a question still drifted through the after-dinner conversation: do you think this might be alive?

This article was written by Sara Cluggage and was originally published in the 2025 Experience Ox-Bow Catalog.